Kyla presenting the Ocean Carbon Observing Science on a Sphere video at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC.

Communicating and Coordinating Science and Policy

Prior to the Knauss Fellowship, my knowledge of ocean observing was limited to the California Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring and Alert Program (HABMAP), a network comprised of nine sampling stations at piers along California’s coast. Each week, scientists collect water samples to analyze the phytoplankton community composition and measure the relative abundance of harmful algal bloom (HAB) species. This network is important for both scientists like me and coastal managers who use this information to protect human and ecosystem health and safety.

For my Ph.D. research at USC, I conducted experiments to study the impacts of climate change on HABs. Though much of this work was conducted in the lab, I often used HABMAP observations to determine when abundances of my study species (Pseudo-nitzschia) were high enough that I could collect samples to use in my experiments.

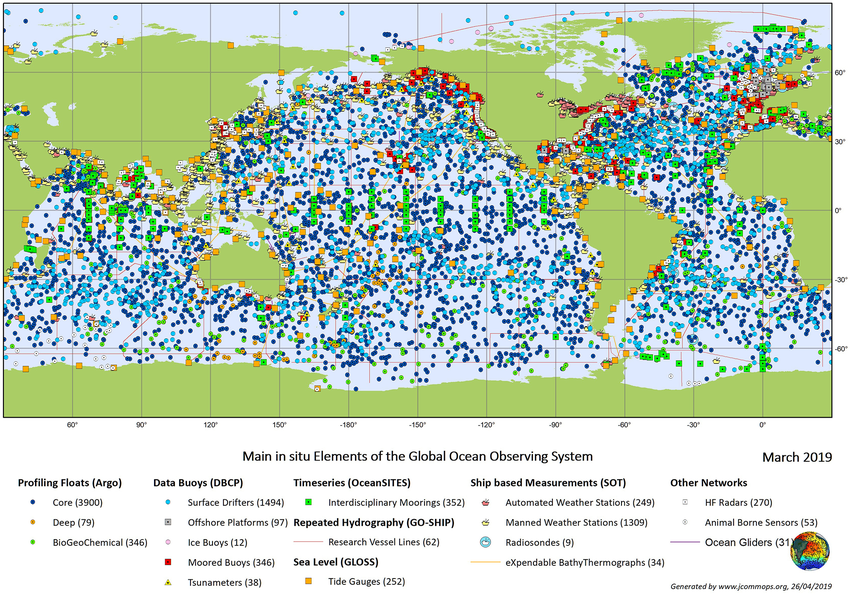

During my time as a Knauss Fellow with NOAA’s Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing Program (GOMO), I learned that observing networks are distributed all over the global ocean to measure physical, chemical, and biological oceanographic parameters. I was surprised and excited to learn that GOMO supports 50% of the world’s ocean observing research! This observational data serves a multitude of societally relevant purposes, including weather and climate forecasts, marine safety and navigation, coastal planning, and improving our understanding of how the ocean is changing and its impact on the environment. This information and research can also help inform policy and management decisions.

Within GOMO, I served as Carbon Coordination and Communication Fellow for the Ocean Carbon Network. This ocean carbon observing system consists of research vessels, ships of opportunity, moorings, and autonomous surface vehicles measuring oceanic and atmospheric carbon all over the globe. These ocean carbon observations are critical for understanding how much atmospheric carbon the ocean absorbs, helping us determine the ocean’s role in regulating the global climate. This knowledge allows us to predict the future climate, prepare for climate-related challenges, and develop policy to help prepare for and mitigate the impacts of change on society and the natural environment.

Coordinating Ocean Carbon Science

GOMO’s Ocean Carbon Network is only one of the many ocean carbon observing efforts within NOAA, and there is a need for improved communication and coordination of carbon observing activities. For the “coordination” piece of my fellowship, I was tasked with leading the development of an Ocean Carbon Observing Science Plan for NOAA’s Ocean and Atmospheric Research (NOAA Research) line office. This plan outlines and prioritizes NOAA Research’s ocean carbon observing goals, as well as provides coordination across NOAA Research and with intra-agency, interagency, and international partners.

To develop this Science Plan, I convened a panel of 16 ocean carbon scientists and program managers from each OAR lab and program to gather information on what these experts thought were the most important ocean carbon science questions that NOAA Research should work towards answering over the next 10 years. We used this information to develop an outline for the plan, producing three goals, each with research questions and actionable objectives that NOAA Research will accomplish in working towards these goals. With the completion and review of the outline, I led the Executive Writing Team to draft the plan. Once the first draft was ready, I planned and hosted a workshop in Boulder, CO, re-convening the ocean carbon scientists and program managers to review and revise the plan.

Facilitating the development, review, and revision of this plan was a large undertaking. In total, over 40 subject matter experts from 25 NOAA and partner institutions contributed and were instrumental in the development of this Science Plan. The document was also vetted by the NOAA Research Oceans Portfolio, NOAA Research lab and program directors, as well as members of the USGCRP Carbon Cycle Interagency Working Group, the Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification, the NOAA Carbon Dioxide Removal Task Force, the NOAA Greenhouse Gas Monitoring Technical Team, and the Ocean Carbon and Biogeochemistry program Scientific Steering Committee. Over the past year, I’ve worked to incorporate over 1300 comments by subject matter experts. It was exciting to see the strong community involvement in and support of this plan.

I really enjoyed being able to lead the development of this plan alongside my wonderful mentors. Through this experience, I gained a thorough understanding of not only ocean carbon observing and science happening within NOAA Research, but also across U.S. agencies and in the international ocean carbon community.

Communicating Ocean Carbon Science

For the “communication” component of my portfolio, I used a wide variety of communication tools to demonstrate the importance of ocean carbon observations. I wrote web stories on the Global Carbon Budget and the Surface Ocean Carbon Dioxide Atlas, and contributed to articles announcing the return of GO-SHIP cruise A13.5 and announcing Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funds used to support ocean carbon observing. These stories were intended to show the general public the latest GOMO-supported ocean carbon science occurring and the importance of ocean carbon observing.

I also developed a Science on a Sphere video. Science on a Sphere is a unique educational tool: a global display system that projects maps of planetary data onto a 6-foot diameter sphere to illustrate earth system science. With over 175 spheres located in museums, aquaria, and other educational settings worldwide, people of all ages have the opportunity to learn about earth system science in an immersive way.

The Ocean Carbon Observing Science on a Sphere video uses GOMO supported scientist data from the ocean carbon network to create visualizations of ocean carbon for the sphere. The video is intended to teach the general public about the oceans’ role in a changing climate and how NOAA observes carbon to detect changes that are relevant to society. I had the opportunity to show this video at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC this spring and to some NOAA Research scientists in Boulder, CO. It has been really exciting to see others share some of my excitement for learning about observing ocean carbon.

Beyond GOMO

After the Knauss Fellowship, I started a position with California’s Ocean Protection Council as a Water Quality Program Manager. I am thrilled that this position blends my scientific expertise on HABs, ocean acidification, and coastal California with my science policy experience from the Knauss Fellowship. I am incredibly grateful for the opportunities provided to me by the Knauss Fellowship and how it has prepared me for the next stage of my career.